Although Neze's country home in the sleepy village of Keyside had been under construction for almost eight years, one would never have thought so, to see the house, which was still no taller than a man. It wasn't the grandness of the master plan that crippled construction, much less the absence of funds for the project; for no Keysider had a more successful enterprise than Neze's Serene Canteen in Lagos. If anyone could afford to build a five-bedroom detached house in his own hometown, Neze could.

Unfortunately, every time the talented cook arrived at Keyside with his savings, he invariably paused for a chinwag and a plate of pepper soup at Comfort's buka. By the time he finally arrived at the decrepit bungalow he'd inherited from his father, it was usually in the company of needy villagers trying to provoke his inveterate compassion into irresponsible charity. He was such a soft touch that his ne'er-do-well brother no longer bothered to make personal appearances: Paddy's creditors brought his latest credit notes directly to Neze for settlement.

Keysiders were practised beggars, although they didn't look the part at first blush. However tragic their faces, their bodies were plump, verging on the gross. They arrived well-dressed, with over-ripe avocados, a basket of oranges and similar thoughtful edibles with which to welcome their illustrious son who had made good in Lagos. They were also a proud people, but hours into their long visits (in the course of which they invariably consumed their own gifts) their desperate needs usually reduced them — and the sentimental Neze as well — to tears.

Margarita for instance always carried her latest suspension slips with her. She was a distant relative of Neze's, but in Keyside that wasn't saying much, for with a population of five thousand and a culture of intermarriage, many people had one blood relationship or the other. She'd had seven inadvertent kids for as many clients. All her children were still in school — but for the eldest girl who was working at Comfort's buka while awaiting her GCE results. Although the light-skinned Margarita had recently retired from the entertainment business, she didn't draw a pension and one or more of her children were usually out of school for unpaid bills. She'd sit silently, with a tragic, tight-lipped air, until Neze was compelled to inquire what the problem was.

He found it impossible to deny his hometown folk.

Even with Ezeta, an old teammate on the Keyside Eleven, it was dangerous merely to ask ‘how are things'? That was invitation enough to be brought up-to-date with the latest tragedy in the ironmonger's life. As lives went, Ezeta's didn't seem that tragic, but the former centre-forward had a knack for putting a calamitous spin on everything. He seemed a successful ironmonger; for instance he'd only recently moved into his own brand-new house. On paper that ranked him somewhat above Neze in status, but by the time a distraught Ezeta explained the rising price of steel, his banker's foreclosure threat and how his ex-wife had turned his bank account into an excavation site — before eloping with his foreman, Neze felt obligated to advance the substantial loan that would clear the mortgage arrears on the ironmonger's bungalow.

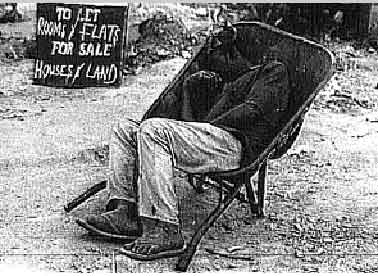

Neze's presence caused Keysiders to degenerate into grievous sighs and long faces — all of which disappeared as the sympathetic cook unzipped his money belt. By dawn, when he approached his construction site, it was usually with a failing heart and a flat belt. He was never able to do much beyond hiring a labourer to clear the rampaging bushes and add a dozen blocks or so to the building-in-progress.

His wife was of a different mould altogether. Keyside folk never figured out how a man as open-handed as Neze ended up with a woman as tight-fisted as Casca. Her mind functioned like digital equipment on which sentimental issues simply didn't register. Yet, she had no particular talent — unless the management of a spendthrift husband was a talent, in which case she was probably deserving of a professorship. Before they met on the eve of Neze's 40th birthday, Neze had been on starvation wages with a Lagos restaurateur, who prevented his workers from resigning by keeping their salaries two to three months in arrears. He lived in a garret and endured all manner of insults from his landlady on account of his perpetually late rent.

Casca had never considered herself a poor cook until she met the man who was later to become her husband. The first time she tasted his beef stew, she'd overeaten massively. She'd spent a painful night rolling on her bed, muttering ‘Witchcraft!' over and over. Thereafter she was ruined for her own cooking. Within weeks of their first meeting, Casca, ten years his junior, determined that they should get married. She also decided he should leave his job and start a canteen in his landlady's disused garage.

Neze's obliging character didn't permit him to deny friends presumptuous enough to ask anything, even when their requests pertained to matters as fundamental as matrimony and career. He usually depended on the impossibility of the requests to maintain his status quo.

Casca overwhelmed him.

Her name meant nothing, being the careless misspelling of a UNHCR official. She was the stateless daughter of a Somalian refugee who was in-between countries when he was clubbed to death for stealing fruits at a local market. She was a foster child of the largest civil service in the world and the life-and-death desperation she brought to her undertakings sapped the will of those who crossed her path.

Neze's impossible landlady found Casca equally impossible to refuse and the laid-back cook had watched with a kind of fascination as the garage was emptied and cleared even before a rent was agreed or paid. The day after he said ‘Let's see how it goes' to her wedding proposal, Neze arrived at work to discover that Casca had resigned for him. She'd also snapped the salary arrears chain by confiscating a box of silver cutlery worth more than his four months' wages. He returned home, not exactly vexed, to find grumbling workmen fitting out an oven for him on credit.

He married her before she developed second thoughts.

Serene Canteen opened. He was a gifted cook and conversationalist; and she was a ruthless manager of man and resources. The landlady, who didn't know what she'd let herself in for, couldn't bear the heat of the oven — or the racket of patrons who kept trooping into her premises well after dark. She allowed herself to be bought out within the year and Serene Canteen ballooned into the main house. Neze woke 4 am daily, including Sundays. He toiled in the kitchen till 7 am when Casca opened the doors of a not-so-serene canteen. He then stripped his gloves to lounge with his patrons, whom he delighted with rib-cracking jokes till they closed at 6 pm.

Neze's conversation was an art form. As between the food and the talk it was impossible to tell what brought more people to Serene. Because of the pressure for seats, customers sometimes dallied over a final spoonful for the half-hour it took a particular yarn to run its addictive course — yet, there wasn't a single day that another glutton didn't howl in pain as he chewed his tongue along with Neze's luscious beef. During the Easter Jollof Night, a wounded customer swore that Neze's beef stew ought to carry a Ministry of Health warning like less pernicious cigarettes.

Casca manned the cash register in the canteen. She was as brusque as her husband was engaging. Even those customers who had been lunching at Serene for a decade didn't qualify for credit in her books. The best an apologetic Neze could do for indignant customers was to slip some extra hot water past Casca to augment their pots of tea.

They prospered.

Sour grapes would say that Casca was too business-minded to conceive, but the absence of children didn't seem to bother Neze. Indeed it was difficult to imagine anything that could bother the genial cook. Even when he returned from his abortive building campaigns to Keyside and Casca raged at the dissipation of their hard-won funds, he'd only shrug: ‘Better to mould cassava blocks in somebody's stomach than cement blocks for Serene Lodge!'

On that eighth anniversary of the foundations of their Keyside house, she could bear it no longer. The housing loan to Ezeta was particularly riling, coming from a Neze whose current family house was a century-old mud hut. She resolved to risk one week's takings in order to safeguard their savings from months of hard work: she left the running of the restaurant to Neze and undertook the week-long trip to Keyside.

She'd initially opposed the Keyside project, thinking it madness to build an expensive house — which would be empty most of year — in a village with abysmal real estate values. Yet a country home in his beloved Keyside was a project of such passionate significance to the cook that his wife had gracefully yielded. By that night when she arrived at Keyside, she'd lost all her reservations on the project. She went straight to the old house to sleep but by morning the news of her arrival had spread, for Keyside was that sort of place. Courtesy callers swamped the cook's wife. She received them over breakfast, listening politely to their convoluted appeals for assistance.

A red-eyed Ezeta was there, with a decree nisi in one hand and a court order for repossession in the other, but the only person who got anything out of her could hardly be called a person, being the dog that nosed through the parsimonious scraps of her breakfast. Within an hour of waking up, she was off to the building site where she spent most of the next week. It was there that Keysiders got to relieve Casca of her money, by hiring their labour to her for wages and earning razor-thin profits from selling supplies to the shrewdest builder that ever laid brick on brick in Keyside. All day and all week, she was buying bags of cement, tipper-loads of sharp sand, headpans of gravel and roofing sheets. Even Ezeta was procured to deliver tons of nails and iron rods; although when it was time to pay him, she shook out her empty purse and asked him to take it out of the over-due loan he owed her husband. She'd left for Lagos before he recovered his voice.

Neze couldn't quarrel with the progress of the house and he never made another visit to the village — until the visit in the course of which he died. The house was completed a few months after Casca took it personally in hand. Being just a five-room house, it wasn't exactly the largest residence in Keyside. On account of his harem, Chief Banjo's palace had almost a dozen rooms; but it was more warren-like than palatial. Neze's well-appointed house on the other hand was built on four levels, with a fenced-in lawn larger than the village's community centre. Beyond sheer size, Casca had brought a design-savvy into the finish of the house that incited neighbours into painting and varnishing their own facades to reduce the aesthetic gulf between the new house and the rest of Keyside. Casca was sufficiently proud of her achievement to do something completely out of character: she suggested a housewarming feast.

Neze's death itself was one of those thoroughly baffling events life threw up time and again. It happened on the eve of the housewarming. The cakes had been baked. The yams, peeled and chopped, were soaking in basins, waiting for the morrow to be boiled and pounded. In the backyard grew a soggy mound of chicken feathers whose dismembered owners marinated in earthenware pots.

Night fell. Neze and Casca were in bed for the night when he remembered a promise to deliver a pot of Jollof rice to the Covent school. It was 10 pm, and she blew some fuses. But without raising his voice, the easy-going Neze could be stubborn in his generosities. Their pick-up fired into life. Fifteen minutes later, it was still idling in the drive and a repentant Casca walked downstairs to urge him on. The cook was slumped in the driver's seat, wearing the puzzled frown with which he confronted eternity.

The next morning, Casca insisted that the housewarming continue in the capacity of a funeral feast. It was a decision that reflected amazing presence of mind, saved her a tidy sum, and had unfortunate reverberations months into the future. The reverend who had been ancillary to the scheduled event suddenly became central to the impromptu one, but he rose handsomely to the occasion. Casca pointed out a spot in the middle of the lawn for Neze's grave. Despite the macabre turn the housewarming had taken, she maintained her composure, nodding sadly at the significant cusp when Neze disappeared underground. She then requested Chief Banjo, who had just arrived, to unveiled the plaque that christened the house ‘Serene Lodge'.

All of which did her reputation no good. Of course, indignant Keysiders had no way of telling that culturally, her nod was the equivalent of their shake of the head — or that her tear-ducts had last functioned, age ten, when she survived the gang-rape by rebels that left her mother and sisters dead.

Within days, she'd put her marriage behind her, shut up the house, and resumed the management of the Lagos canteen. She hired the best cook she could find, and, to avoid too funereal an atmosphere, took to wearing gray rather than black behind the cash register. She struggled for one month but it simply wasn't working. The business haemorrhaged cash. It wasn't just that the quality of the food had crashed, which it had, or that the canteen lacked a foil for the commercial fire of Casca's presence behind the cash machine, which it did. The core problem was that the canteen's regulars resented Casca's cavalier handling of them like mere gullets equipped with wallets. They had voted with their feet. Nightly, Serene Canteen grew more and more serene. The few loyal customers talked perpetually about Neze. The canteen was steeped in the despondency of a wake, which, aside from scaring off new custom was inimical to digestion.

One night, the canteen's auditor interrupted a heated quarrel between Casca and the third cook since Neze's demise. His black bag produced, first a red-streaked analysis sheet, then a terse offer from a buyer. It didn't take long to persuade Casca that the canteen would fetch more as a going-concern than as bric-a-brac in a boot sale.

Casca sold.

The failure of the business, so soon after Neze's death, destroyed her. She'd always known that the business would have gone bust within a month of her predeceasing Neze. She had never dreamt that the converse was true as well. She'd weathered the loss of her family and her spouse. She'd survived the loss of her innocence as a child, but it was the loss of her pride as an adult that spun her into a severe midlife crisis. Yet, with the proceeds from the canteen's sale, she could afford to indulge depression. She slunk home to Keyside and pulled the gates of her hermitage shut after her.

If the truth be told, Keyside wasn't near the top of her list of venues for a hermitage. Yet the riverside village was so isolated that the only possible buyers of Serene Lodge were the residents of the village, none of whom could have paid for the house, even if it were auctioned at a tenth of its value. Although she had nothing in common with the villagers, Serene Lodge was the only root she had, anywhere in the world. She lived a quiet, self-sufficient life, aloof from the villagers, doing her shopping in nocturnal drives to Benin.

However, if she succeeded in putting the villagers out of her mind, she remained uppermost in theirs. On a daily basis, She was the subject of simultaneous conversations around Keyside. Serene Canteen was the ‘Crown Jewel' of Keyside and the news of its sale swept Keyside like a tsunami, provoking a rash of gossip in the village. The jigsaw puzzle of Neze's life came together in a popular picture that fired Keyside's collective indignation. Chief Banjo considered himself above gossip, but he had little control over the sessions that took place in his lounge, especially after his guests had indulged his potent akpeteshi brew.

'She got him cheap.'

'Dirt cheap.'

'She ought to be arrested! Are there elders in this village or what?'

'But there's no evidence, only supposition…'

'Suppo? Suppo-what? A woman has the effrontery to organise her husband's burial feast even before murdering him and you're still suppositing. No, it's not supposition, call it suppository!'

'I'm not siding her; I'm just talking about evidence that can stand up in court.'

© Chuma Nwokolo, Jr.

but not a room for siesta.